— by Vivienne Blandford —

This is a very broad-brush comment about a landscape led approach which compares the type of archaeological features that have been mapped/visualised by LiDAR on what are essentially are two chalk landscapes, Cranborne Chase and the Chilterns. Both are landscapes that also contain other natural features much influenced by their geology. These include chalk streams, river valley bottoms, heaths and woodlands. In such a short article no one archaeological feature can be explored in any great detail, more than in acknowledging whether a feature is present or not.

The Beacons of the Past project was initially set up to find out more about the Chiltern’s Iron Age Hillforts and their prehistoric chalk landscapes. A lidar survey was flown which covered 1400 square km over the Chilterns National Landscape which possesses, as the introduction line to the Chilterns website states: ‘possesses unique geological, ecological and cultural heritage features.’ It contains a diverse archaeological landscape which includes iron age hillforts, field systems dating from that time, medieval field patterns and remnants of woodland heritage as in charcoal hearts and sawpits, mostly undated but post medieval.

However, the Chilterns is a relatively wooded landscape, with a higher percentage of ancient woodlands than is usual. It is also well known for its beech woodlands. Archaeological features often survive better in woodland, whether ancient or replanted woods, rather than in open land where they may have been ploughed out or become less distinct.

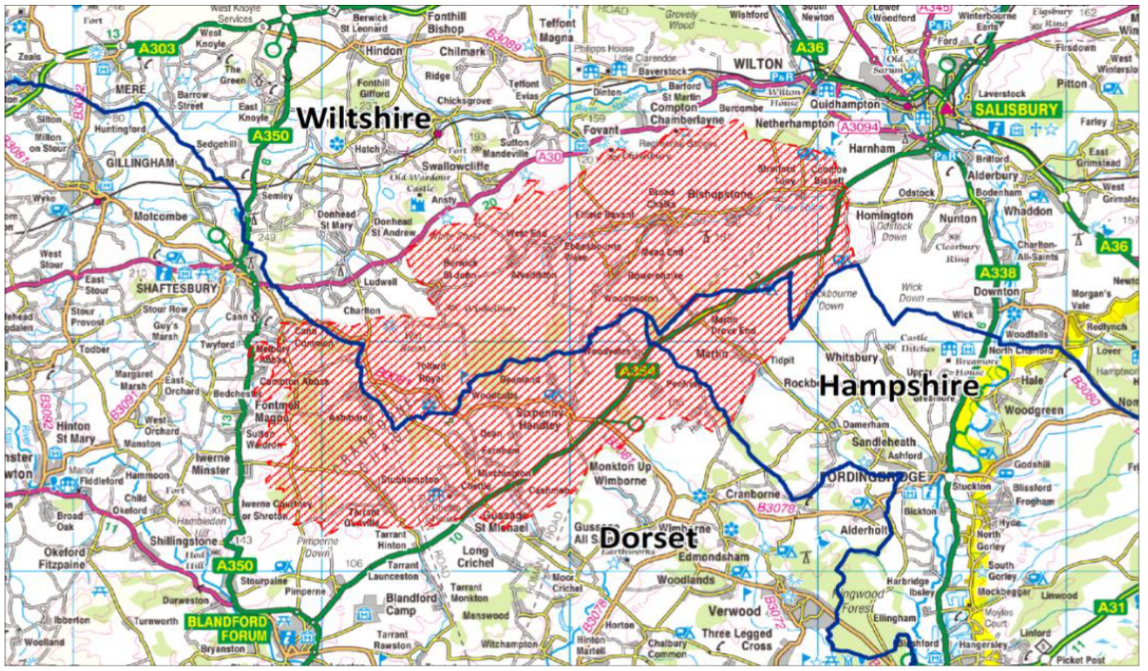

The Chalke and Chase Champions of the Past aimed to use LiDAR to gather new archaeological information about the heritage of Cranborne Chase and Chalke Valley area. It was already well known for its wealth of prehistoric sites, from neolithic through to the Iron Age on the chalk landscapes but had also been known as a royal hunting reserve, whereby it had got its name. It is much less wooded in the present day, than in the past and the landscape has continued to be used for arable and pasture rather than big estates replanting the landscape with woodland. This area too has its share of chalk downland, chalk streams, valley bottoms and woodland and, it too, encompasses a diverse archaeological landscape, but perhaps it is later land use that dictates the difference in archaeological features that have been identified in the two landscapes?

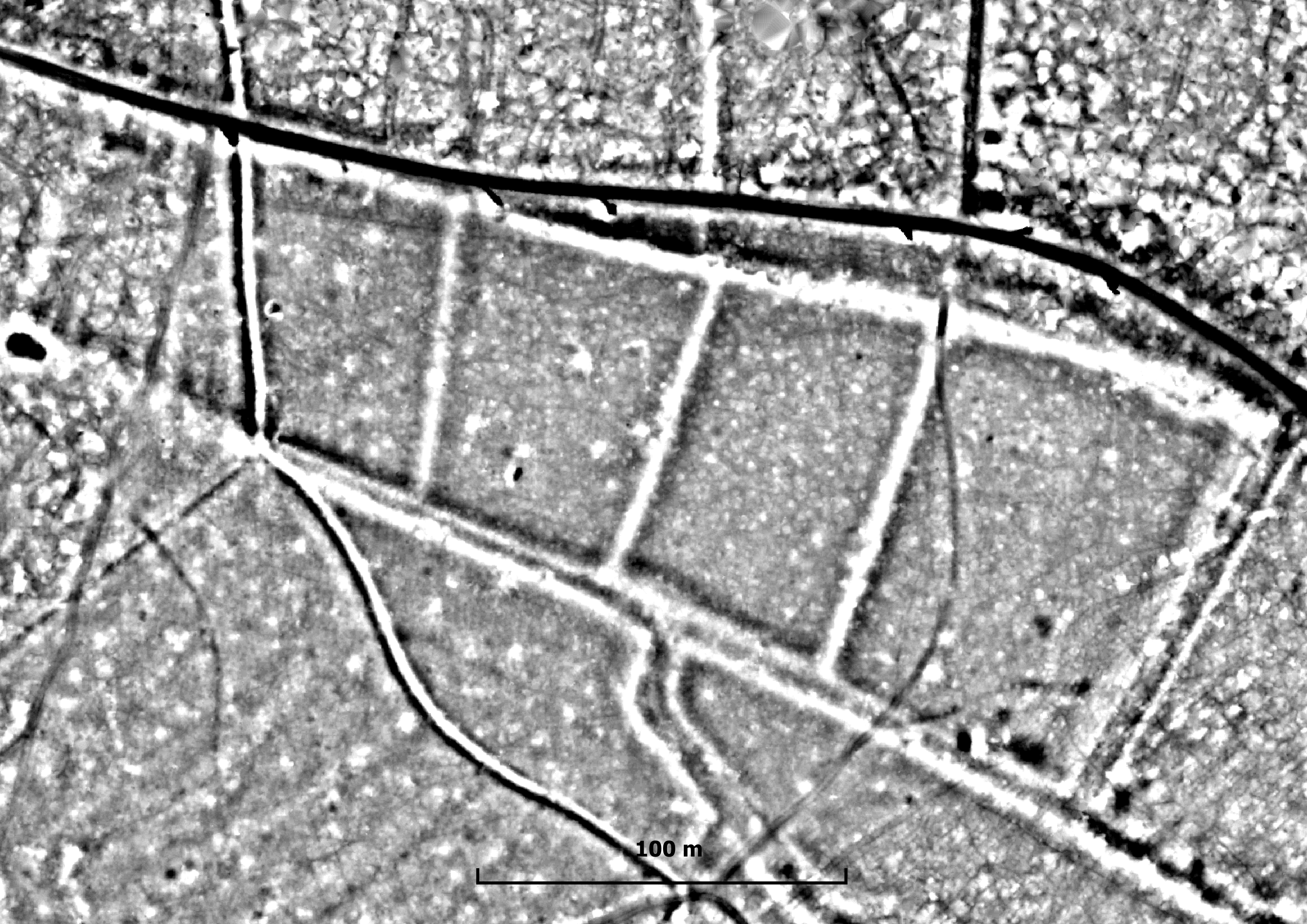

However already well known the archaeological features were, a LiDAR survey gives a unique perspective in being able to visualise these features from a landscape perspective. Often it is impossible to actually find these features on the ground. So, briefly the similarities are the myriad of field systems, some associated with known Iron Age sites. Some field systems are co-axial with their own routeways connecting them, some seem an uncomprehensible jumble of banks, some detail lost through time, change in land use and ploughing.

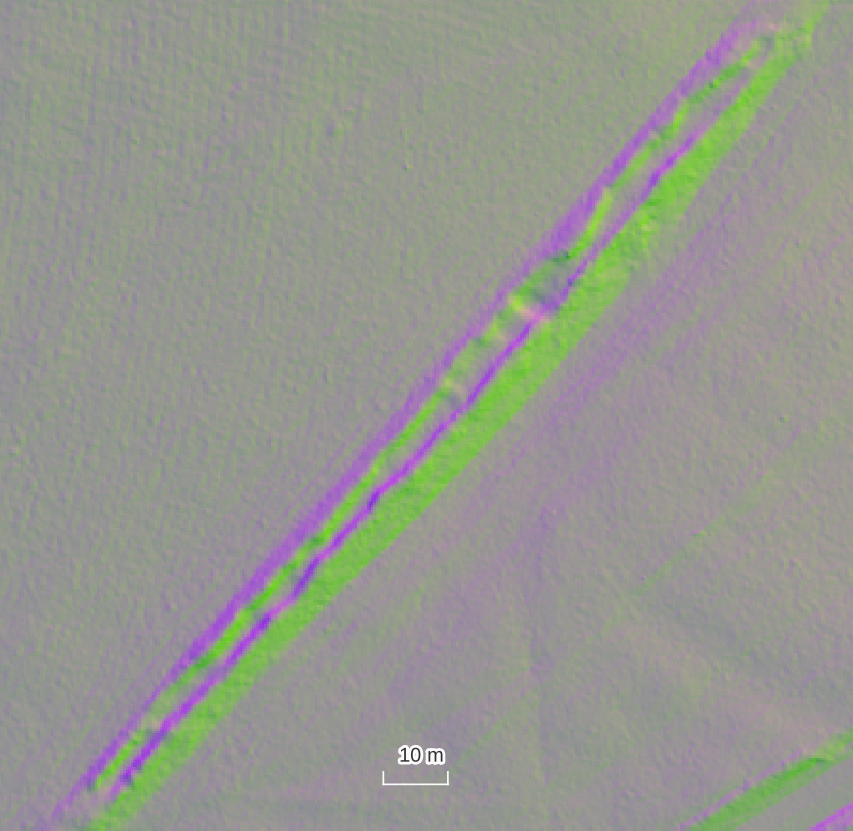

Roads, some datable, as in the Roman roads, others drove ways, survive well in both landscapes. Some still in use, some fallen out of use, but visible, once again in the lidar images. Other field systems are medieval to post medieval some as lost parts of medieval settlements, though not necessarily as deserted medieval villages, just shrunken ones. Possibly C18 onwards both areas saw water management features alongside their clear chalk streams with watercress beds, some of which appeared on the early ordnance survey mapping.

Apart from the enigmatic pits, regularly spaced and very similar in shape and form, on lidar, and the military features Chalke and Chase seems to lack the later archaeological features that figured significantly in the Chilterns. The Chilterns has numerous chalk pits but lacked the uniform spacing and appearance of those found in the Cranborne area.

The Chase lacks pillow mounds, one good example, found at Pimperne, where four atypical pillow mounds can be seen contained within a much older field system. Over 45 examples were found in the Chilterns. Pillow mounds, known from medieval times, became popular again late C18 through to the C19, were used to house farmed rabbits, initially for fur but later to eat. All examples are likely to be post medieval.

On the Chilterns the most extraordinary number of saw pits were found within the wooded landscapes. But most of the saw pits were probably associated with the previous century woodland management of the wooded estates. Have any been found in the Cranborne Chase area? Other features associated with woodland are charcoal pits, often linked to early industry but charcoal was also used a s a domestic fuel. Interestingly few were identified in both areas although it was said there were charcoal pits in Chiltern woodlands, they were not identified on the lidar images.

It would seem that from prehistoric to medieval times the use of the two landscapes were broadly similar from the lidar analysis carried out, which only ever tells part of the picture. Later, alternative practices to agriculture were exploited in the Chiltern landscape but not so in Cranborne Chase. This is a topic the deserves wider research.