— by Vivienne Blandford & Rebecca Bennett —

When considering the nature of the pits we have identified in the LiDAR of the Chase it is useful to compare their pattern and form to chalk pits in other areas. Chalk extracted in this way was commonly used for spreading over fields to improve the soils.

All of the ‘marl pits’ we have been looking at in the Chase area are fairly small, which begs the question “why?” In open land it could be seen as more efficient to dig a large hole in one place rather than many smaller holes. The pattern perhaps indicates that they value the land / extracted materials differently to how we might at first imagine and not desire a single large quarry or see the benefit of economies of scale for this process. Perhaps the smaller pits we see in this area are reflective of an earlier economy where they could be dug and managed by a few people to a shallow depth and easier to get the material out.

Woodland or Farmland?

I have done quite a bit of work in woodlands across the south east of England and from what I have understood, the woodlands were a valuable resource, and it is unlikely that most quarry pits were dug in contemporary woodland. Usually, the woodland came later. Sometimes whatever industry/ agriculture caused those pits to be dug had long since ceased and we are looking at woodland succession.

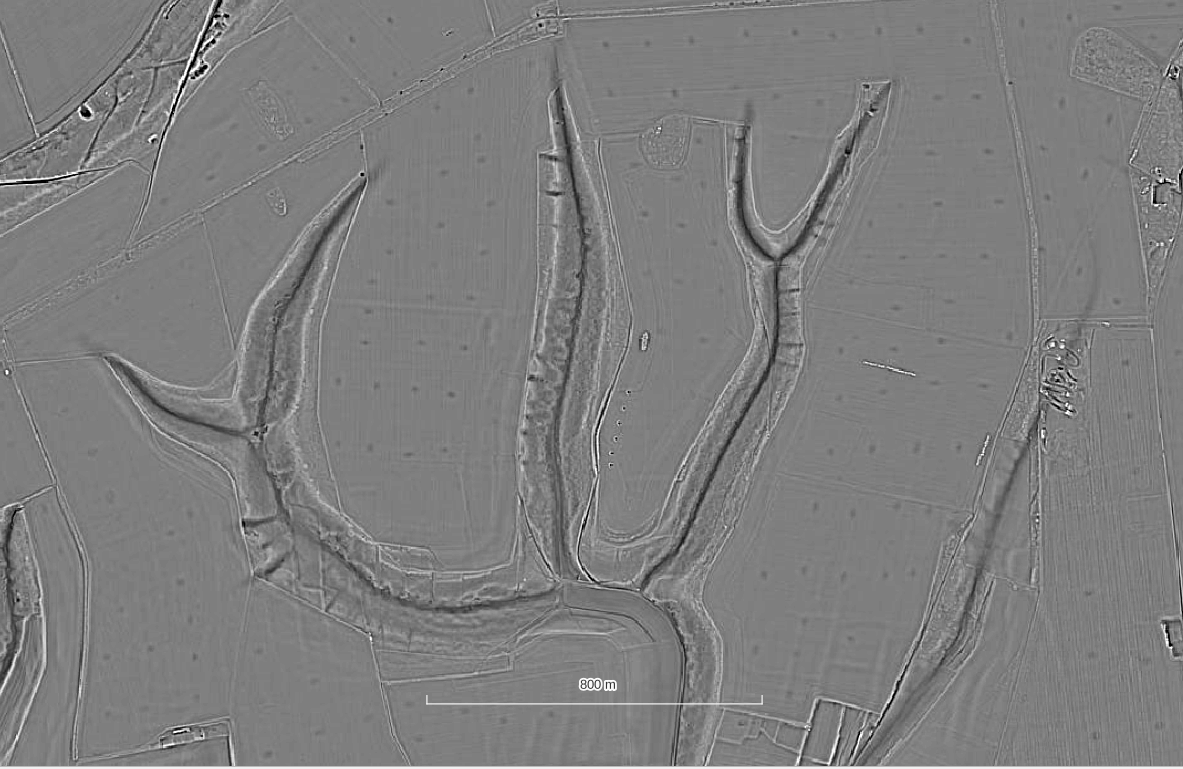

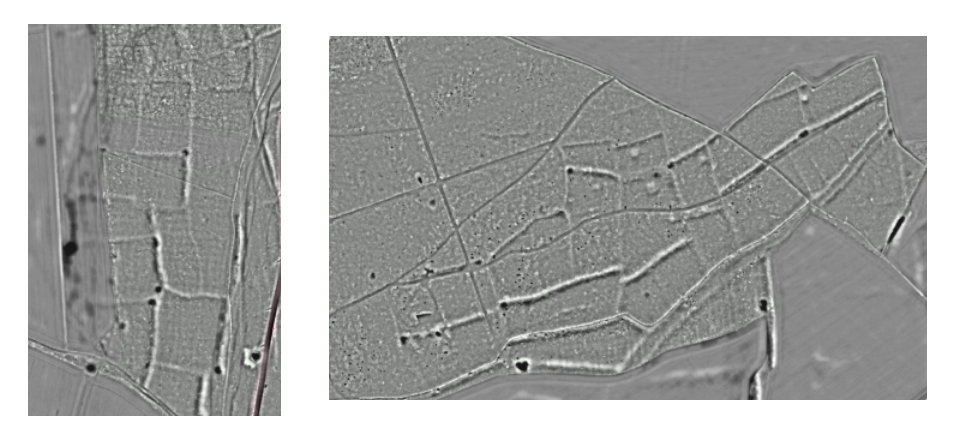

Pits and Prehistoric Boundaries

Chalk pits are a common feature of English chalk landscapes and in areas such as the South Downs have been noted to be closely associated with prehistoric field boundaries, particularly where these intersect rather than the very regularly spaced pattern seen in the Cranborne Chase area. This makes some sense as the chalky material built up in the field banks would have potentially been easier to extract than digging into the chalk directly.

Chalk Wells

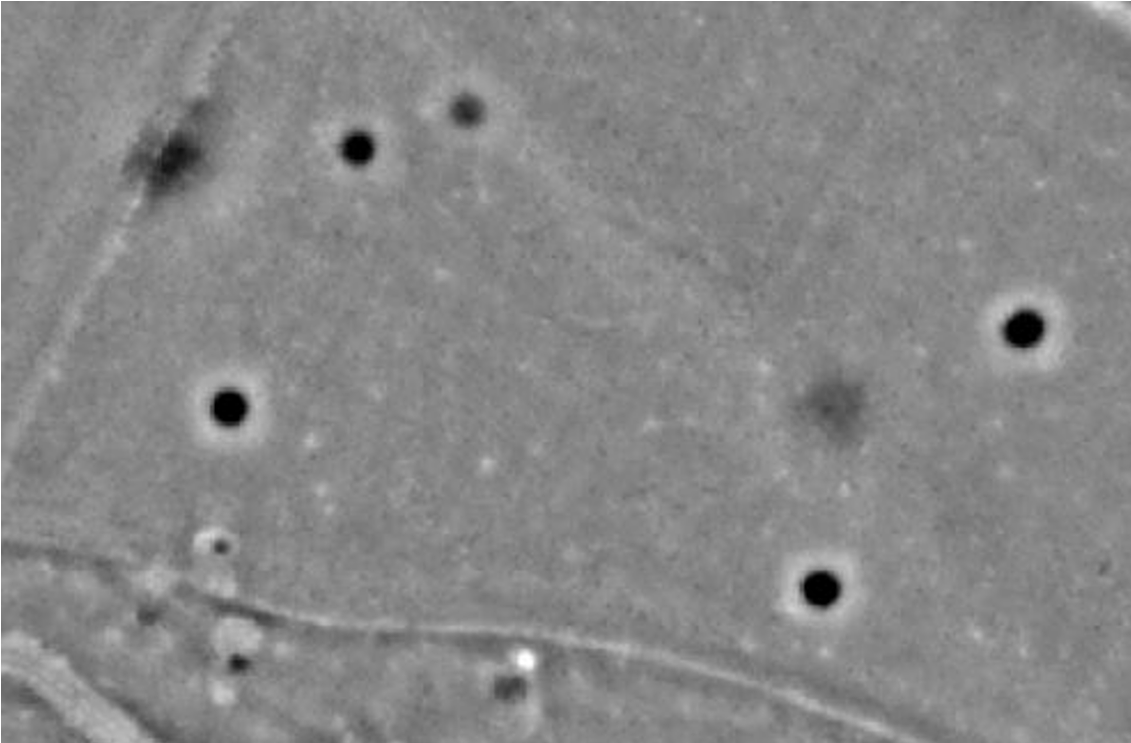

In the Chilterns lidar project a number of chalk wells were identified. These were spread out in the open fields are numerous, almost perfect circles which vary from 5m to 10 m in diameter with a possible ring of spoil around the outside, although this might be exaggerated by the effect of LRM imagery, very regular in size and shape. Other circles appear as fainter ‘black holes’ of roughly similar size. They are likely to be the same feature, just more ploughed out and less deep.

The spacing of these pits in the Chilterns seems to be fairly random. These are all likely be “chalk wells” which were cut with steep shafts some 30 feet deep. Whatever type of quarry/pit they are features which have no obvious form of access.

The wells seemed to be mostly worked during the 18th and 19th centuries and written accounts describe how it took three men to cut the Chalk and raise it in baskets tied to a rope that ran over a pulley and windlass. Once dug they are a hazard to the unwary as they could be 30 feet deep, so they were covered, but not always effectively as the covers can fail and the shafts can unexpectedly re-appear! This small-scale method of obtaining chalk/lime less would be less destructive in the landscape than large open quarrying.

The pit features in the Cranborne chase area do not seem to match the circular pattern of the chalk wells, being more oval and broader in nature, indicating extraction of shallow deposits rather than deep ones. However no examples of the pits have been excavated so their depth and profile is unknown.