— by Yvonne Crossley —

I first became interested in LiDAR maps of the Burcombe landscape when I found iron pyrites nodules on a walk around the top of the Punchbowl near Netton Clump. What were they? What was the geology of the high plateau? This was in 2020 before the Chase and Chalke projects had even begun. Then I discovered the open LiDAR data from the Environment Agency (1995) and noticed all these regular pits along the high chalk plateau.

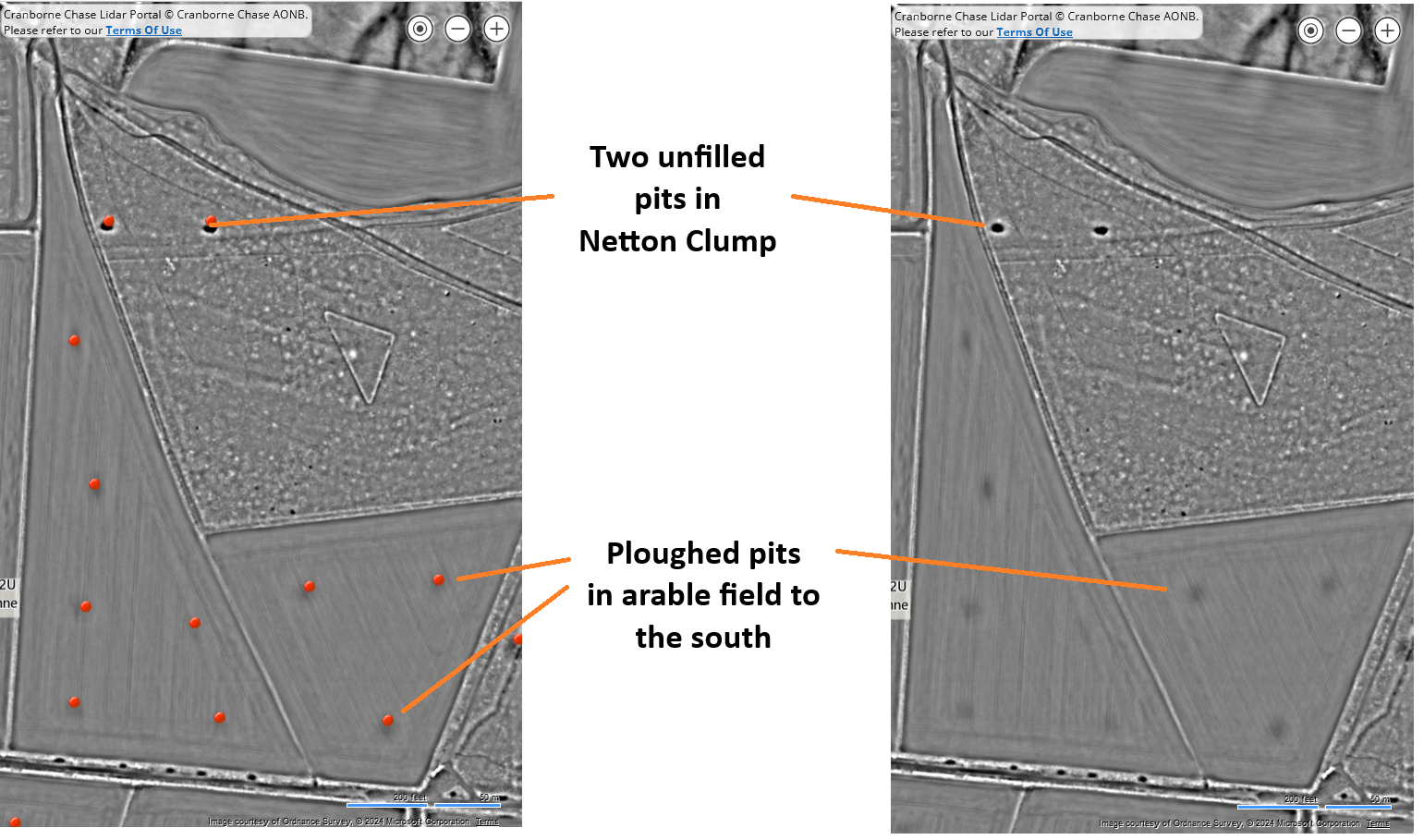

Roll on to 2023/4 and having signed up to training for LiDAR mapping with the Chase & Chalke Champions of the Past project and then Chalk Pit mapping, I decided to investigate the area of Netton Clump and its two adjacent fields. A site visit early in 2024, when vegetation was low, resulted in photos of the slight pit impressions still visible in the fields. They corresponded well to old Ordnance Survey maps and detailed LiDAR data we had access to. Venturing into the wood, we also found the two unfilled pits still visible today. Historically this Douglas fir plantation was probably a later addition to Wilton Estate woodlands and might give an indication of pit age.

Other research on geology, Wilton Estate enquiries, maps and archaeology records did not provide definitive answers but lead me to suggest these pits were there before the Victorian Ordnance Survey maps were produced. They often relate to areas of clay with flint nodule geology, and digging here must have involved a large amount of manual labour. Locally, mining for and preparing gun flints was a known activity in the Salisbury area (John Aubrey 1656-1691 Nat. Hist. of Wilts; also Fowler and Needham WANHM Vol 88, 1995 p137-141). Soil improvement, using clay as a marling material, may also have been undertaken. The flint nodules themselves may have been dug for flint wall building or flint working, and the clay for daub?

Netton Down’s boundary with the common fields to the south is difficult to place. It

Gough, 1979

was also inclosed by the Act of 1792. If it is assumed that the common down extended

a little further south than that in Bishopstone Manor then the total area would have

been about 360 acres which compares reasonably well with the estimated 400a of

1567 when the north, east and west bounds (with adjoining manors) are similar.

By 1843 only about 40a, remained unploughed

When we consider agricultural usage, this area was once primarily grazed by sheep and then ploughed for cereal growing after 1792 (Gough, 1979). Research from Iron Age/ Romano Britons excavations indicates smaller pits were dug for many reasons, but it appears no specific archaeology has been undertaken on these larger pits, 20 – 30 m, slightly oval. Enquiries at Wilton Estate Office produced no pit working records. A reference in: Tree planting history of Grovely, by A C Caceres, 2018, refers to Douglas fir planting starting after the First World War in nearby Grovely. An online search located helpful information on land use: Pamela Gough 1979 PhD, University of Birmingham: Continuity and Historical change in Woodland and Downland in an area West of Salisbury, Wiltshire.

The word Netton relates to cow (neat) and I would surmise that cows were kept here. Large flocks of sheep were known from both medieval Wilton Abbey records of Washerne and Harewarren and Bishopstone Manor records, listed by Gough. The siting of ridge top barrows on Burcombe Down and Harewarren also point to an open grassland landscape in the Iron Age and Durotriges era. Geological studies suggest solution hollows are sometimes found, yet this cannot explain the number and spaced arrangement of these pits, many being of uniform dimension and shape. The Netton Clump pits were about 2m deep x 10 m x 6m, only partly re-filled and planted with fast growing trees. The field pits were measured on Chalk Pit LiDAR mapping portal as in 20 – 30m size range.

Conclusion

The pits were dug after the Inclosure Act of 1792 (and perhaps disenfranchisement of Cranborne Chase by 1829) for purposes as yet unknown; Netton Clump woodland was planted on open downs, probably in the early 1900s. The field pits were ploughed over once sheep became less profitable and cereal production increased.